I still remember one of the first moments of my college orientation at UCLA in the summer before my freshman year. As a first-generation student, this was one of my few times on a college campus—it all seemed so intimidating. I felt nervous as my fellow students and I were ushered into one of the big lecture halls on this big campus. I am pretty sure I sat somewhere in the back. The orientation speaker talked for a moment about UCLA, welcoming us to one of the finest public schools in the nation, part of the renowned University of California system. Then, after these brief salutations, the speaker asked a question that I will never forget: “How many of you want to go to graduate school?” I looked around me at all my new peers who immediately raised their hand high in the air, my head on a swivel. I think I was one of the only students to not raise their hand. I did not even know what graduate school was. I was just happy to be at this place called “college.”

***

Fast-forwarding to the present, as a professor at UCI, it is a tremendous privilege to teach such brilliant, ambitious students. Making sure that my courses are rigorous and intellectually stimulating, while remaining engaging and structured are foundational principles of my pedagogy. I care deeply about making sure my students develop their academic skill sets—writing, advanced-level thinking, communicating, and beyond—so that they can be successful in their field of choice. For those who have followed my workshops at DTEI, you might know that I make frequent use of technology and digital tools to advance these goals, ranging from the use of Padlet and Mentimeter, to Prezi, to Hypothesis. However, as the first person in my family to receive a four-year degree (and of course, advanced graduate degrees as well) perhaps even more important than these tools is to make sure that my pedagogy supports UCI’s large first-generation population. Nearly half of all UCI undergraduate students are first-generation, with UCI being the top choice for first-generation students for the fifth year in a row. Thus, considering the demographic of students I teach—and remembering my own struggles many years ago—I still tell this story of orientation on the first day of every class.

As faculty, no matter how organized our Canvas spaces are or how innovative our pedagogy might be, it is vital to make sure that our classroom and our broader instructional approach is accessible to all the students we teach. For example, research shows that first-generation students often have a lack of institutional knowledge that many of us faculty probably take for granted—all of which can lead to academic disengagement. (Consider how you might assume students know the meaning of “office hours,” but many students have no idea that this is a time for them to visit you.) While first-generation students bring with them abundant amounts of aspirational capital and belief in the power of higher education, they can see institutions like UCI as traumatic places due to their unfamiliarity with the college landscape. This unfamiliarity can create disconnects between faculty and student expectations. Many first-generation students are less likely to know the importance of networkingand less likely to pursue internships. I can say from personal experience that first generation students are also often more hesitant to speak with faculty or ask questions—after all, meeting people with PhDs for the first time and being called “Dr.” can be intimidating! Moreover, first-generation students of color are even more likely to experience obstacles to their success, such as feeling a lower sense of belonging in college in comparison to their peers who have family members with college degrees. Although the experiences of first-generation students across race, ethnicity, class, and gender are very different, ultimately, it is important that we as faculty understand more broadly the unique experiences of nearly half of the student population we teach—and then craft our pedagogy accordingly. After all, my course is only as rigorous and useful in terms of knowledge-building as the level of investment returned by each student.

In my teaching, I think carefully about how I can make my course as “student friendly” as possible to first-generation students (and all students). The more accessible the course is, the harder they will be motivated to work, and ultimately, the more they will learn. Thus, over the years, I have implemented a number of “little” practices that have helped my first-generation students feel welcome, supported, and empowered to collaborate with their peers and reach their fullest potential. I also understand that restructuring a course can be daunting (and time-consuming), and so, even just implementing these small things—I believe—can go a long way in supporting first-generation students:

- Renaming “office hours” to “student hours.” As I previously mentioned, attending office hours can be among the most daunting experiences in college! Over the years, I have had hundreds of students come to my office hours and tell me that their visit is the first time they ever visited a professor’s office hours. (Many of these students were seniors too.) I remember feeling extremely anxious when I went to speak with a professor one-on-one when I was an undergraduate student. On the first day of class, I explicitly make clear to students that these “student hours” are for themto meet their professor, and that they do not have to have a question—they can even just come to say hello. Just changing the wording from “office hours” to “student hours” on my syllabus and Canvas space can be a way to make this intimidating experience more accessible and clear. For a bonus tip, try hanging some signage that is welcoming, too!

2. Provide “reading notes” for students prior to assigning texts. When I was an undergraduate student many years ago, I remember the amount of reading—and the anxiety of figuring out how all these readings connected to class content—was one of the biggest adjustments in college. Still, I continually hear from students that they struggle with readings. To help, I provide “reading notes” that frame the assigned texts while providing why they matter and how they connect/build/support class content. I have heard from students this has helped them engage more with my assigned texts and be more prepared for class discussions.

3. Provide really clear rubrics. This might sound obvious, but having very clear and detailed rubrics makes a big difference! While creating rubrics—and I do so through Canvas—can be tedious, from my experience, they are immensely helpful in helping students understand the expectations for each assignment. I think we can sometimes take for granted that students just “know” what is expected whether it comes to writing an essay or completing a project, but for many first-generation students, all of this is new and providing extra clarity increases positive outcomes.

4. Make a “who to contact and how to get help” page. Each quarter I teach multiple courses with 125 students each, and the stack of messages I receive from students can be overwhelming. It can also be confusing for first-generation students in terms of who to contact regarding an issue. Do I contact the professor? The Teaching Assistant? The Grader? The Peer Assistant? Thus, on the front of my Canvas home page, I create a separate page of when to contact each individual, depending on the question or issue. While not all students are going to follow these instructions, it can be helpful for first-generation students who are trying to understand all these different personnel and receive quicker help.

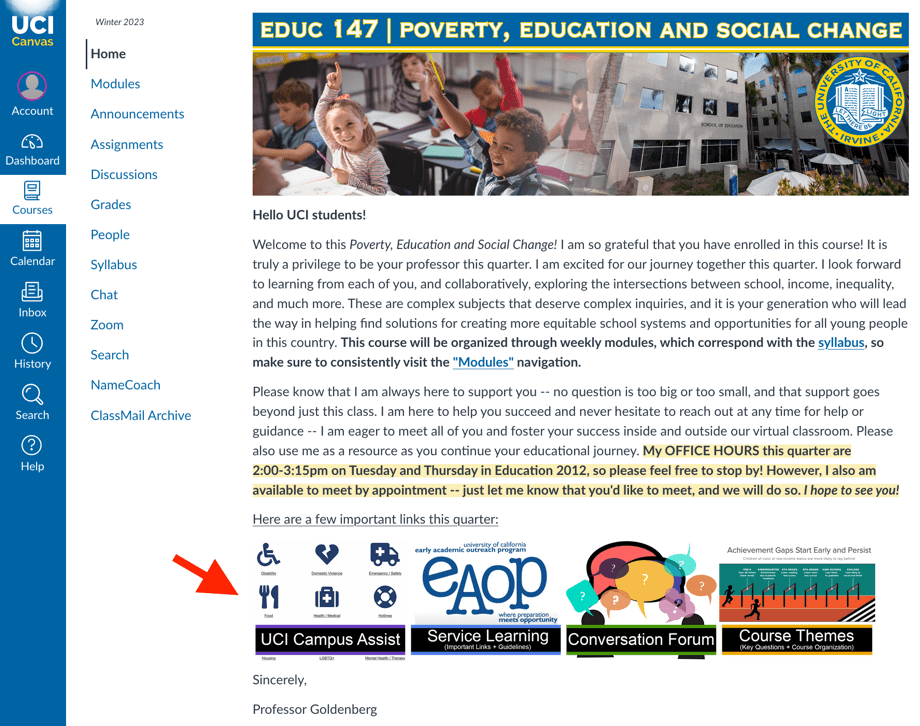

5. Provide a link to UCI resources. We are fortunate that there are a myriad of wonderful resources to help students succeed in college, ranging from mental health resources to food assistance to counselors and social workers ready to provide support when necessary. However, I have found that many students are not at all aware of many ways that they can receive support—and this is particularly true for first-generation students who are already trying to adjust to college. Without the institutional knowledge or a family member to speak to, many first-generation students frankly have no idea that there are so many resources available to them and that colleges provide these sorts of support systems. I can recall countless instances where a student would ask me or a teaching assistant for help regarding a personal issue, without realizing that they already had access to people and services. To remedy this, on my Canvas home page, I have a prominent link to the amazing “Campus Assist” website at UCI, which clearly lists the dozens of different resources. If there are resources specific to your department such as access to tutoring, a peer advisor, or a social worker, just taking a few minutes to put that material on your Canvas home page can make a huge difference. Students can only perform their best academically if they are physically, mentally, and emotionally well. In addition, it also shows your students that you care about their well-being—and, as a mentor once told me, no one cares what you know, until they know that you care.

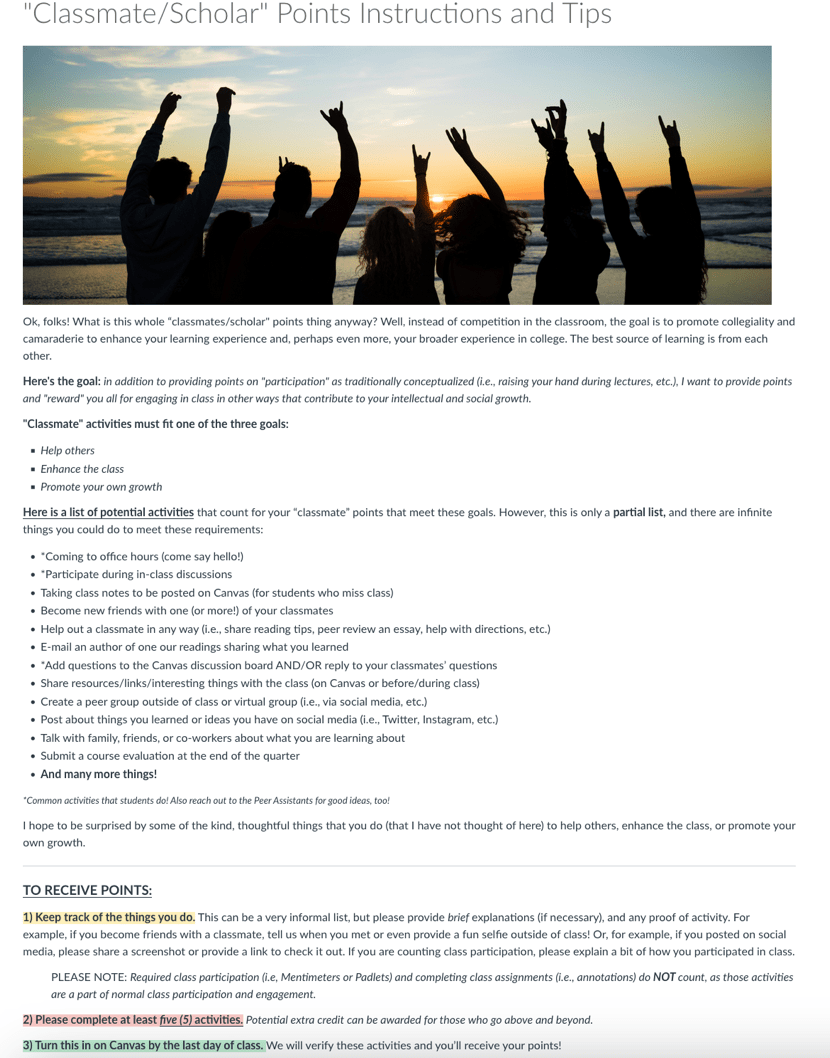

6. Create structured, low-stakes opportunities for peer-to-peer interaction. Some of the most common sentiments of first-generation students are feelings of isolation and detachment. It always breaks my heart when students tell me that they do not feel connected to campus or have few peer friendships. Since first-generation students are significantly more likely to also be low-income students, they are also more likely to commute and not live on campus. Therefore, they have less opportunities to create meaningful relationships with their peers. While we all have our different philosophies around assigning group projects—and students’ opinions differ greatly, too—I believe it is extremely important for faculty to create structured and gently-coercive moments of collaboration. For example, in my big lecture classes of 125 students which can be particularly intimidating for first-generation students, I assign what I call “Scholar/Classmate Points”: a low-stakes assignment, conducted over the course of the quarter, in which students receive points by, in part, helping out a classmate (or contributing to the course more broadly) or meeting peers from the class. At the end of the quarter, students turn in a list of “activities” they have completed for points. Although they are not weighted very heavily in my course, even attaching a few points to these activities encourages students to meet each other. In addition to the many in-class group activities, countless students have shared with me over the years how they have met some of their best friends at UCI through my class and have felt more connected to their peers.

8. Share your story and your educational journey. Again, this might seem like a simple exercise, but from my experience, it makes a huge difference! For us in academia, it is normal to be around those with advanced degrees and to see higher education as part of our daily lives. But, for first generation students—including myself many years ago—many see faculty as so far away from the “norm” and internally wonder: “How did they get there?” By sharing your educational journey, your struggles and challenges, and just a little bit about your own life, students will be able to better connect with you, better understand your expectations, and see you as a faculty member committed to their success and personal growth.

To be sure, these suggestions will help all students feel more empowered and interested in their academic agency, but none more than first-generation students who are still adapting to such a sprawling, world-class institution such as UCI. I would also encourage you to learn about the excellent resources available at the UCI First Generationwebsite if you would like to further explore ways to support your first-generation students.

Coming full circle, when I sit back and reflect on my own educational journey, I would never have guessed that the young student sitting in orientation all those years ago, anxious about whether I even belonged at a University of California campus, would one day be teaching at one. It was only thanks to professors and mentors along the way who believed in my academic abilities and my well-being that I am here today. It is our job to make sure that, in addition to creating the most streamlined Canvas courses and utilizing technology in ways that induce rigor and engagement, we create a classroom atmosphere that allows first-generation students to reach their full potential and share their brilliance with the world.

About the Author

Barry Goldenberg

Barry Goldenberg

Lecturer, School of Education

Barry Goldenberg joined UCI during the pandemic in 2021, and his teaching excellence is well-recognized on campus within a short amount of time. He received the 2022 Lecturer of the Year and also was nominated for the 2022 Learning Experience Design and Online Teaching award at University of California, Irvine.

Besides Barry’s content-areas interests in the history of education, community schools, educational equity, and multicultural education, his work is deeply intertwined with the belief that scholars should work to bridge the gap between the academy and the communities we research. He was involved in the Youth Historians in Harlem (YHH) project exploring these boundaries through collaboration with young people and our shared pursuit of knowledge production.

Barry believes firmly in the brilliance of our youth — and always center his research around the idea that we underestimate their enormous, untapped potential. He strives to be a critical theorist and idealist with a stream of pragmatism; a deeply engaged citizen; a dedicated educator and listener; and a committed writer.